The decision by Mediaworks to axe its long-running prime time current affairs offering, Campbell Live, seemed like the end of era to many loyal viewers. Although the ‘review’ was announced in April 2015, the outcome seemed inevitable when it transpired that MediaWorks had already curtailed its sponsorship deal with Mazda back in February. The news inspired a petition comprising over 75,000 signatures and public demonstrations on a scale not seen since the closure of TVNZ7 back in 2012. The final broadcast in May 2015 saw tears shed both on and off the screen. It has been replaced in the 7pm slot on TV3 by the more populist Story, while Campbell himself is now presenting Radio New Zealand’s Checkpoint.

Although the discontinuation of Campbell Live became a cause célèbre, it is important to evaluate the issue in the broader context of an ongoing decline in news and current affairs right across the media ecology in New Zealand. As such, the decision should be understood as a symptom of deeper structural problems, including the financialisation of news media, intensified competition across the value chain in response to convergence, and efforts to consolidate and restructure news production.

Campbell’s advocacy on social issues (notably the Canterbury earthquake rebuild and Pike River mining disaster) doubtless irked some of the politicians and corporate actors being held to account. Reports that John Key had commented that “I want that left wing bastard gone”[1], coupled with circumstantial links between National Party MPs and MediaWorks management led some blogosphere critics to suspect MediaWorks’ decision was politically-motivated. Such allegations are difficult to prove, but they are unnecessary to account for the decision to axe Campbell Live.

MediaWorks’ internal review document reveals management’s concern over ratings in the 7pm slot which, despite the temporary increase during the review period, had been slipping over the past couple of years, and, perhaps fatally, slipped below 200,000 in March 2015.

MediaWorks management wanted to reformat their 7pm current affairs slot to deliver a larger, more diverse audience through to the 7.30 slot. The review document also noted that changes would include ‘greater editorial oversight by news leadership’, ‘stories not to go past the point of audience fatigue, e.g. Pike River’, ‘stories to be carefully evaluated if there is legal risk’, and ‘story mix to include a greater emphasis on entertainment’. The review also found John Campbell remained the most popular presenter. Although head of news and current affairs, Mark Jennings (who has since left MediaWorks after 25 years), sought to retain him as co-presenter, Campbell himself confirmed that he felt it was an offer he could not accept.

The drive for more populist and less critical news and current affairs formats reflects the priorities of MediaWorks management, most notably ‘reality-TV Queen’ Julie Christie, former boss of Eyeworks Touchdown. Having been appointed to the board in 2013, Christie’s role was extended to include responsibility for TV and video strategy shortly before the Campbell Live review was announced. It appears that tensions ensued when management attempted to dissuade the Campbell Live team from continuing their coverage of the Canterbury earthquake aftermath and the Pike River mining tragedy and include content that would link into TV3’s reality-TV offerings such as The Block[2]. TV3’s new 7pm slot programme, Story, is certainly more aligned to the format envisaged in the review, and although its ratings are currently no better, they comprise a higher ratio of the more lucrative 25-54 demographic.

However, concerns over the decline of ‘hard’ news and current affairs pre-date the controversy over Campbell Live by at least two decades[3]. Commercial pressures on news media have certainly intensified since 2005 when TVNZ, during its ill-fated Charter period, replaced the long-running Holmes with Close-Up. This is what encouraged TV3 to compete directly with Campbell Live (followed by Prime TV after acquiring the services of Paul Holmes)[4]. However, a combination of technical, market and regulatory factors have combined to render the contemporary media ecology far more hostile to commercially sub-optimum genres in prime time.

Since then, ‘harder’ current affairs content such as TV3’s The Nation and TV One’s Q&A has been completely relegated to Sunday mornings, where advertising restrictions means low ratings incur no opportunity cost. Opportunity cost here refers to the relative expense incurred by a broadcaster when it schedules a more expensive/less profitable programme instead of a cheaper/more profitable alternative. Meanwhile, TVNZ’s replacement of Close-Up with Seven Sharp in TV One’s 7pm slot entailed a comparable shift toward ‘light’ current affairs interspersed with banter and opinion from the presenters, albeit without triggering public protests.

This trend is not limited to television. Media convergence has altered the logic of media business models right across the value chain. Although the fragmentation of audiences and revenue streams on traditional platforms should not be overstated, the intensification of competition across the value chain (including content production, aggregation and distribution) means that even relatively small margins of profitability are vigorously contested. Media dependent on advertising have been particularly susceptible to these pressures because a wider range of operators are competing for a finite pool of revenue.

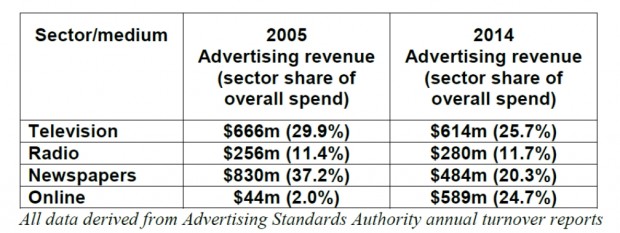

As the table below indicates, the newspaper sector has been hit particularly hard. Declining revenue has driven newsroom cuts, restructuring and reporter casualisation. Although television and radio advertising revenues have proved somewhat more stable, in the absence of any regulation of cross-sector competition or media ownership, they are facing increased competition for both eyeballs and content rights from subscription providers (both direct transmission satellite and online).

In addition to these system-level pressures, MediaWorks has had its own institutional challenges. In 2007, CanWest sold MediaWorks to Australian private equity fund, Ironbridge Capital. Private equity funds are significant for two reasons; first, they often seek short-term returns on assets, and second, they are not subject to the information disclosure obligations of publicly-listed companies. Ironbridge leveraged its buy-out and placed the debt onto the company just prior to the downturn stemming from the global financial crisis. Servicing the debt proved unsustainable, and in June 2013 MediaWorks went into receivership – expediently avoiding $22m of tax obligations and cancelling an expensive overseas content rights contract. Oaktree Capital, another private equity fund, subsequently took a controlling stake. The 2014 appointment of former NZX head Mark Weldon as CEO suggested improving revenues in preparation for stock floatation was the over-riding shareholder priority.

The relentless drive to optimise returns across every slot in the schedule has seen a recent merging of MediaWorks radio, television and online news production into Newshub. This mirrors moves by other media, notably NZME’s amalgamation of its print, radio and online news units, but the ulterior motive is to reduce costs. This saw the departure of Mark Jennings and the appointment of Hal Crawford from NineMSN, whose dismissive comments about leaving ‘quality journalism’ to die evidently align with the commercial production values espoused by Julie Christie and Mark Weldon.

Meanwhile, several other current affairs programmes have been restructured, rescheduled or replaced. TV3 declined a further series of Media 3 after two seasons (although Maori TV now carries Media Take). This was followed by the cancellation of Third Degree in April 2015 and, after several schedule reshuffles, its successor 3D was also discontinued. The fact that programmes can be dropped even when NZ On Air subsidies are available to off-set opportunity costs attests to the commercial pressures driving commissioning and scheduling decisions. This pattern of events would suggest that the fate of Campbell Live was by no means an isolated incident, but a symptom of a deeper structural trend.

Managerial antipathy to factual content of any substance is certainly one factor here. However, for a commercial media operation answerable to private equity shareholders, it is no longer sufficient for a programme to rate well enough to cover costs and make a return on investment – its margins must be commercially superior to alternative content options, which may entail cheaper and less popular content but with higher returns. As Campbell himself remarked back in a 2012 interview, ‘We’re on TV3 at 7 o’clock- it’s a brutal time-slot, man- brutal!’ Looking back at the MediaWorks’ decision in the context of the regulatory, technological, and financial factors outlined in this Paper, perhaps the most remarkable issue is that Campbell Live survived as long as it did.

[1] The suggestion that Campbell was politically biased is questionable, especially considering the infamous 2002 ‘Corngate’ interview with Helen Clark: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1dET78Z5b5s

[2] Communication with anonymous MediaWorks source.

[3] See Atkinson, J. (1994). Structures of Television News. In P. Ballard. (Ed.) Power and responsibility. (pp. 43-74) Wellington: Broadcasting Standards Authority. Also see: Baker, S.J. (2012). The Changing face of Current Affairs Programmes in New Zealand 1984-2004. AUT PhD Thesis. Retrieved 31 October 2015 from http://aut.researchgateway.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10292/5552/BakerS.pdf?sequence=3

[4] See Thompson, P.A. (2005) Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Out. NZ Political Review 54: 44-49