One of the interesting trends of the National Government’s budgets has been how it has been able to raise tax revenue practically unnoticed. Attention has largely focused on income tax rates and, to a lesser extent, the applicable thresholds. However, away from the spotlight various budgets since 2009 have made apparently minor “adjustments” which cumulatively add up to quite significant changes.

For example, the 2011 budget made employer contributions to KiwiSaver schemes subject to employer superannuation contribution tax and halved the maximum credit payable to KiwiSaver funds. Those changes were estimated to be worth $513 million to the government in the June 2012 year, rising to $720 million for the June 2015 year. The 2012 budget increased the student loan repayment rate from 10 percent to 12 percent from 1 April 2013, widened the definition of income for repayment purposes and removed the voluntary repayment bonus. These measures were worth $230.8 million over four years.

In addition, over the past twenty-five years governments of both hues have used inflation or “fiscal drag” to increase tax revenue by not annually adjusting income tax thresholds. As wages rise taxpayers move into higher tax brackets increasing the tax take. Fiscal drag also enables governments to promote changes to thresholds as “tax cuts” when in fact they represent little more than inflationary adjustments.

(By contrast New Zealand Superannuation is index-linked as are the lower and upper thresholds for Accident Compensation. The income threshold at which student loan repayments commenced used to be inflation-adjusted but was frozen at $19,084 in the 2011 budget. This threshold was left unchanged for six years until 1 April 2017 when it was increased to $19,136.)

As income tax thresholds had not been adjusted since 1 April 2010, the expectation prior to the budget was that these would be increased at least in line with inflation. Based on the Reserve Bank estimates of wage inflation since 2010 the new thresholds could have been as follows:

| Tax rate

|

Current threshold

|

New threshold

|

| 10.5%

17.5% 30% 33% |

$0-14,000

$14,001-48,000 $48,001-70,000 Over $70,000 |

$0-16,600

$16,601-57,000 $57,001-83,000 Over $83,000 |

According to Treasury’s estimates, the annual effect of fiscal drag is an additional $1.9 billion paid in income tax.

The other consistent approach of the National Government’s budgets has been to give with one hand but take with another. The income tax reductions in the 2010 budget were offset by a 20 percent increase in the rate of GST from 12.5 percent to 15 percent. Similarly, the benefit changes announced in the 2015 budget were accompanied by changes to the abatement regime applicable to Working For Families. Under the abatement regime the amount of Working For Families’ credits receivable are reduced (abated) as income rises.

In fact, Working For Families has been the subject of some very dramatic changes. The 2011 budget broadened the definition of income for Working For Families’ purposes, reduced the income threshold at which abatement applied from $36,827 to $36,350 and increased the abatement rate from 20 percent to 21.25 percent. The 2015 budget increased the abatement rate again to 22.5 percent from 1 April 2016. This year’s budget reduced the threshold for abatement from $36,350 to $35,000 and increased the abatement rate to 25 cents in the dollar from 1 April 2018. This change had been signalled in the 2011 budget but was not to be operative until 2025.

The effect of the changes to abatement thresholds and rates, combined with the broader definition of “income” can be seen in the following Inland Revenue statistics:

| Average entitlement | Number of families entitled | |

| 31 March 2009

|

$6,615

|

402,800

|

| 31 March 2019

|

$6,628

|

415,100

|

| 31 March 2011

|

$6,464

|

421,200

|

| 31 March 2012

|

$6,563

|

398,700

|

| 31 March 2013

|

$6,731

|

379,000

|

| 31 March 2014

|

$6,726

|

364,000

|

| 31 March 2015

|

$6,788

|

347,300

|

Despite New Zealand’s population growing by over 274,000 between December 2008 and December 2014, the number of families entitled to Working For Families’ credits has fallen by over 55,000 since March 2009. As Inland Revenue noted in its 2016 Annual Report (p. 47) the changes to eligibility in 2011 now mean “there is very little correlation between households with dependent children and Working For Families registrations.”

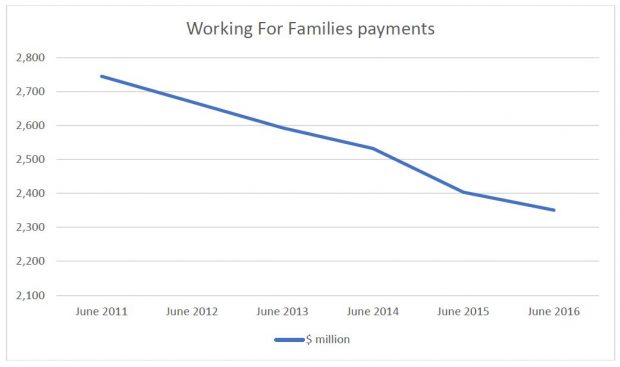

The combination of greater abatements, and a fall in the number of families entitled to claim Working For Families, has resulted in a fall in the total amount of Working For Families’ tax credits paid by Inland Revenue. Between the June 2011 year and June 2016 the total fell by over $393 million from $2,745 million in 2011 to $2,351 million in 2016[i].

As the entitlement to Working For Families is income dependent, recipients can be overpaid if income exceeds estimates. Recipients who are overpaid must therefore repay it, not an easy proposition for low-income families. As a consequence, the amount of overdue Working For Families’ credits rose sharply after the June 2008 year before Inland Revenue got it under control.

Against this backdrop, the 2017 Budget is therefore a classic National Government budget involving an apparent giveaway in the form of increased income tax thresholds, a rise in Working For Families’ payments and the Accommodation Supplement. These are matched by the withdrawal of the independent earner tax credit and accelerated changes to the Working For Families’ abatement regime.

The budget means that from 1 April 2018 the effective marginal tax rate for someone receiving Working For Families and earning $40,000 is a hefty 43.89 percent (17.5 percent income tax plus ACC of 1.39 percent and the 25 percent Working For Families abatement). For those with student loans add another 12 percent and that’s an effective marginal tax rate of over 55 percent. If that person is also receiving Accommodation Supplement (also subject to 25 percent abatement) and contributing the minimum three percent into KiwiSaver, then their effective marginal tax rate is an eye-watering 83.89 percent. In other words, for every additional $1 earned in wages or salary, the worker is only 16c better off.

The 2017 budget will bring some relief to earners but for those on lower incomes and receiving Working For Families the gains may appear somewhat illusory once the impact of abatements is taken into account. What it highlights is the troubling interaction between tax and social assistance and a need to overhaul the current system.

Terry Baucher has co-authored a book called Tax and Fairness, available here: http://bwb.co.nz/books/tax-and-fairness

[i] Data compiled from Inland Revenue Annual Reports 30 June 2011 to 30 June 2016 inclusive, available at http://www.ird.govt.nz/aboutir/reports/annual-report/