The Briefing Papers were launched in 2014 with the aim of providing the public with an overview of critical issues facing New Zealand society in the 21st century. Drawing on long established traditions of scientific advice the briefing paper series has sought to build a platform of expertise in public policy by engaging leading researchers and commentators from both the public and private sectors.

Throughout 2014 the briefing papers canvassed a wide range of public policy issues with the aim of promoting informed discussion and debate so crucial to economic and social development with the central question being: How is the public interest being served? The public interest is central to policy debates, politics, democracy and the nature of government. It is a key factor in assessing jobs and the cost of living, housing options and the way in which the policy makers of today are protecting the interests of future generations.

The briefing papers will continue to be posted on these issues throughout 2015 with an innovation to the series being launched this week by framing major issues on a monthly basis and then posting a cluster of papers aimed at exploring different facets of these issues or events. The first series of papers in February will centre on Work & Wages to coincide with the hosting of a seminar by Professor Guy Standing on Friday the 27th of February. Professor Standing is an internationally renowned economist who previously led a major programme for the International Labour Organisation that produced the ‘decent work index’ and more recently as a Professor at the University of London where he has established the Basic Income Earth Network.

Work & Wages have been at the heart of social policy concerns in this country since the Liberal period when New Zealand passed the Industrial Conciliation and Arbitration Act and enshrined a basic minimum wage in legislation. The aim was to provide families with a decent living according to the colonial standard. The ‘family wage’ not only established a basic minimum income for the majority of households but it protected wage rates and conditions and it included provisions for sickness leave and overtime.

It was a distinctive approach to social policy that was extended in the wake of the Great Depression to encompass free primary and secondary education, a community-based preventative health scheme, a salaried medical service, a free public hospital system and a state housing programme for those who could not afford a home of their own. The combination of a family wage and full employment dominated social policy in this country for over 50 years with home ownership being particularly significant both as a stabilising influence and as a central element in a family’s economic and social security.

The fulcrum of social policy in this country was the full employment of working age males and throughout the post World War Two period we were particularly successful. Just how successful came home to me when I was presenting a seminar in Europe in the 1980s. The Director of the Swedish Institute endorsed my account of New Zealand’s success by highlighting our employment record. He explained how he was comparing unemployment rates across the OECD countries during the 1970s with rates ranging between 3% and 14% of the labour force. When he came to New Zealand the figure he was given was 13 which he thought was very high until he realised that the New Zealanders were talking about the number of people unemployed not a percentage of the labour force. I have previously quoted the unemployment rate in March 1956 when there were 5 people registered as unemployed and the Minister could say with a certain conviction that he ‘knew the unemployed by name’.

As we all know that has changed driven initially by the vulnerability of New Zealand’s pastoral economy and a breakdown in this country’s access to the British market coupled with a significant decline in the family wage and a major shift in the labour market as women entered the paid work force. But the major changes were driven by a small cabal of Treasury, business and political leaders, inspired by the Chicago School of Economics and the theories of Hayek and Friedman. In the 1980s this right wing cabal introduced an extreme form of economic fundamentalism that went further than ‘Thatcherism’ in Britain or ‘Reganomics’ in America. The policy prescriptions were similar.

Jobs were cut – incomes were reduced – state services were withdrawn – and the increasing costs of health, education and community care were transferred to families in general and to women in particular. The cumulative impact of these policies resulted in severe damage to the tradeable sector. Profits, employment and investment were all affected and export growth sharply diminished.

Investment in New Zealand manufacturing declined by almost 50% between 1985 and 1989 and by 1991 registered unemployment represented 11% of the total workforce. Long-term unemployment became a serious social problem with the unemployment rate for Maori aged 15 to 24 years approaching 40%. In 1991 these socially bankrupt policies were taken to their illogical conclusion. Substantial cuts were made in benefit levels and other forms of income support effectively redefining poverty in absolute terms. In 1981 almost 115,000 people were in receipt of a welfare benefit – by 1985 that figure more than doubled and by 1992 it had trebled. The very policies that were designed to cut welfare expenditure created the largest pool of beneficiaries since the Great Depression.

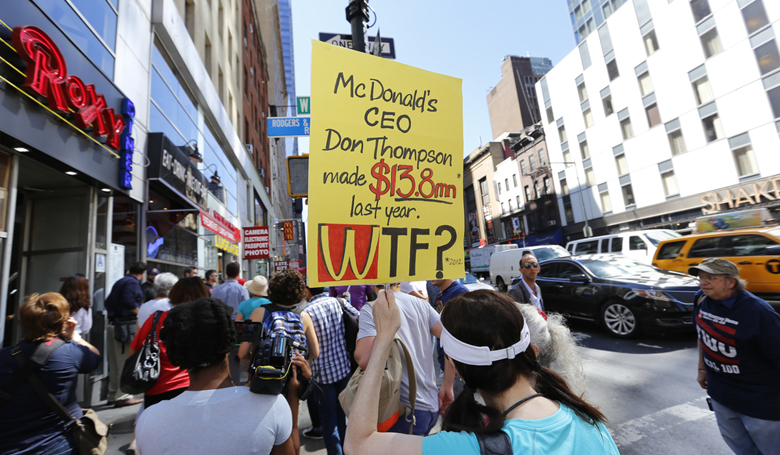

But as Professor Standing suggests the impact of the reforms implemented by many ‘developed’ countries during the 1980s and 1990s have escalated well beyond what used to be referred to as frictional unemployment and welfare dependency. What has emerged are precarious societies dominated by gross inequalities and job insecurity. Standing argues that inequalities are becoming unsustainable as the ‘rentier’ economies of the 21st century support a tiny elite that is gaining income from the system while the growing ‘precariat’ is facing falling wages, unstable labour, and increasing economic and social insecurity

This is certainly true of New Zealand where the family wage has been replaced by an incoherent set of policies that favour those in full-time employment over those on benefits, the healthy over the sick, childless households over households with children and those who own multiple properties over those seeking to buy or rent a home.

From the mid 1980s to the mid 2000s OECD figures record that New Zealand had the developed world’s largest increase in inequality with an estimated 285,000 children living in poverty today. Of particular concern are figures from the Ministry of Social Development that reveal 50% of the children in hardship come from working families. For those excluded from the labour market OECD comparisons show that benefit levels in New Zealand are now among the lowest in the OECD relative to average wages. The strategy of driving down wages and benefits has failed increasing numbers of New Zealanders.

Indeed the low wage economy and its punitive approach to welfare benefits have merely exacerbated the precarious nature of work and the vulnerability of its citizens. What is required according to Professor Standing is a new form of social compact and a new charter designed to ensure greater security. That is what this series of briefing papers are designed to do – to address the precarious nature of work and wages so that these issues will not need to be dealt with by future generations.