We’re now having a fractious debate about foreign buying of houses, but the more important and tougher debate we should be having is about migration.

Does it actually generate the right type of long term economic growth, or does it just pump up house prices and interest rates, suppress wages and reduce the incentives for New Zealanders to obtain the necessary skills for a modern economy?

Neither of the three biggest parties, National, Labour or Green, have challenged the consensus of at least the last 15 years that New Zealand needs plenty of skilled and unskilled migrants to juice the economy along.

There are plenty of employers who regularly argue that they need both types of migrants to keep their businesses, hospitals, hotels and farms running and growing. The Government has a target of allowing around 45,000 to 50,000 new permanent residents each year, including around 60% who are skilled migrants, over 32% who are family reunifications and over 7% who are approved for humanitarian reasons.

It may argue that one reason for high net migration is the uncontrollable movements of New Zealanders and Australians (who are often ex-pat New Zealanders), but that’s not the whole truth. The Government does control that Residence Programme and various schemes for international students, working holiday visas and seasonal workers.

Over 300,000 migrants have arrived over the last 15 years encompassing the current National and the last Labour Governments.

Understandably, New Zealanders see themselves as the descendants of migrants in one form or another who have an open and welcoming approach to new migrants. That is all good.

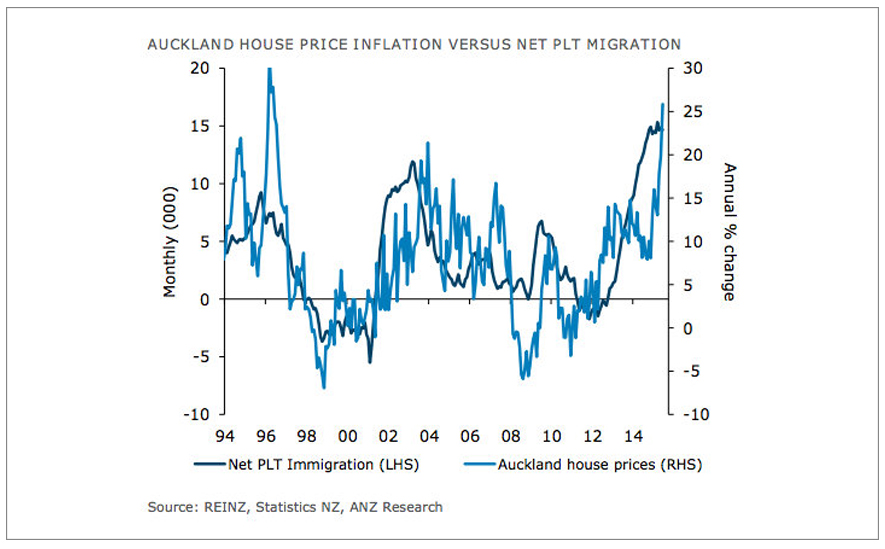

But migration that is too fast can put a strain on the economic system and the key variables of interest rates, the exchange rate, house prices and unemployment show the stresses involved of the latest migration surge. When there are restraints on the supply of houses, schools, motorways and hospitals, as there are in Auckland, then prices and interest rates respond.

Former Reserve Bank economist Michael Reddell pointed last week to Reserve Bank modelling showing a 1% rise in population will lead to a 10% rise in house prices. Last year Reserve Bank and Treasury separately forecast that a surge in net migration to over 45,200 and over 41,500 respectively would increase the Official Cash rate by between 50 to 100 basis points and increase nationwide house price inflation by four percentage points.

Net migration alone is increasing New Zealand’s population by more than 1% per year at the moment and that’s before natural population growth adds to the pressures.

“Rapid population growth and a low responsiveness of supply have led to housing and urban infrastructure constraints,” the OECD concluded in its report on New Zealand earlier this year.

All this creates costs for taxpayers and ratepayers alike because the infrastructure costs and rent subsidies triggered by net migration has to be paid for with higher rates and taxes. Auckland’s ratepayers may blame the Auckland Council for their near-10% rates increase this year, but they could just as easily blame New Zealand’s migration policy makers.

The other costs are borne by the rest of New Zealand’s businesses and exporters through interest rates and the exchange rate being higher than they otherwise would need to be. New Zealand has had strangely high long and short term interest rates over the last 20 years relative to the rest of the world and there’s a strong case that our high migration is at least partly to blame.

The other losers are resident workers and the unemployed because the high net migration has helped suppress wage growth and kept unemployment stubbornly high at over 146,000 or 5.8% of the workforce. This may be as good as it gets.

The latest migration tweaks announced last weekend show how responsive the Government has been to the calls from employers to make it easier to solve their labour shortages by importing workers. The rule change to allow long term migrants on temporary work visas in the South Island to apply for permanent residency is one example.

Wage growth has been much lower than everyone expected in the last two years, which is at least partially due to strong net migration soaking up the pressure that would otherwise have been applied to wages.

It also begs the question: why can’t we train or educate some of those 146,000 unemployed for these jobs? Is the Government and society collectively taking the easy option of migration to avoid the much crunchier problem of ensuring kids graduate from schools and tertiary institutions with the literacy, numeracy and life skills needed for these jobs?

Turning full circle, the migration debate is also inevitably intertwined with the debate about foreign buying of houses. New Zealand may discover after October 1 when the tax residency status of buyers will be recorded that much of the money being pumped in from overseas is going through the accounts of new migrants, students and those on short term work visas, all of which would be recorded as local buying.

Ultimately, taking pressure off house prices, interest rates and unemployment will require lots of hard work to improve the supply of houses and skills, but in the short term a debate about the number of migrants is needed.