There are a number of challenges facing the building industry in Auckland, around scale, quality, efficiency and price. Scaling up the building sector raises questions: What are the crowd-out risks for other sectors in Auckland, as the building sector tries to outbid them for labour and materials? How can public policy better support industry to meet various sectors’ needs?

Policy makers have a number of initiatives to help gear up industry for major expansion, including:

- the ‘Building and Construction Productivity Partnership’ (since ceased)

- MBIE’s ‘National construction pipeline’ (latest issue was July 2015)

- ‘Workforce skills roadmap for Auckland construction’ to support skills sector growth.

Recent analysis commissioned by the Council suggests house prices are high because of anticipation of redevelopment opportunities enabled by the Proposed Unitary Plan once it becomes operative.

Builders and tradespeople may move from Christchurch to Auckland as the rebuild ramps down, but capacity challenges will remain.

Productivity

There has been little, if any, measured productivity growth in New Zealand’s construction industry for over 30 years. (One problem is measuring the quality improvements that result from productivity growth.)

The cost (excluding land) to build the average 200m2 house is not far off $400,000 — about five multiples of Auckland’s median household annual income (of approximately $80,000). Contrast this with the ideal ratio of three to one, including land.

The Productivity Commission in its 2012 Housing Affordability inquiry attributes low productivity growth performance in the residential construction industry to:

- structure:

- the industry’s small scale and lack of scale economies

- fragmented industry structure requiring a myriad of subcontractors and informal contracting

- skills issues

- conduct:

- low levels of innovation

- ‘bespoke’ (tailored) nature of our homes

- inferior management skills and practice (e.g. project management)

- councils (as building consent authorities) being excessively risk averse and stymieing innovation in design, materials and construction techniques.

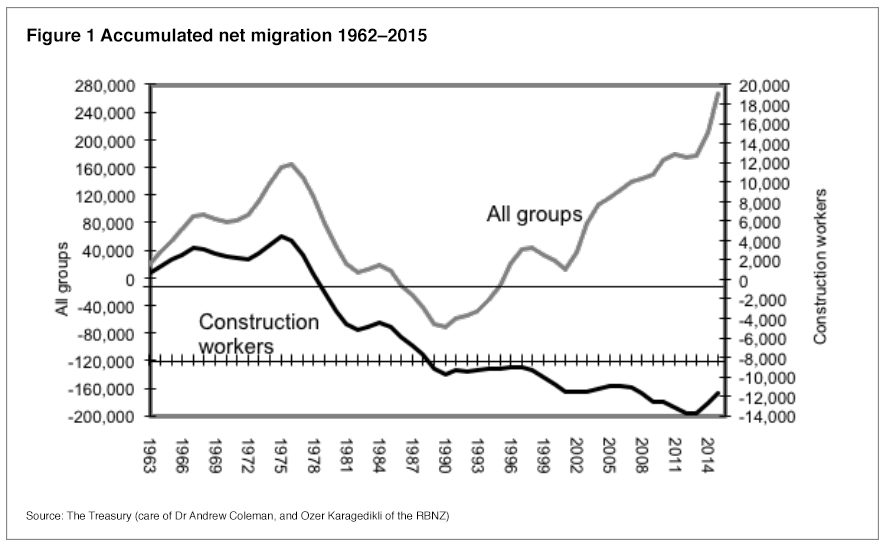

Poor retention and attraction of workers

New Zealand has an issue with attracting and retaining builders and tradespeople internationally, as the figure below shows:

Builders advise that this is caused not by barriers to entry, but because it is an unattractive field to be in this country these days:

- low wages — from low productivity

- punitive liability rules — 10-year personal liability and joint and several (rather than proportional) liability

- too little initiative afforded to builders — building inspectors do not afford builders with much leeway to use initiative and deviate from plans because of concerns about quality assurance.Poor project management and quality assurance

Work that I co-led last year for the Productivity Partnership found that project management was:

- generally poor (but with pockets of excellence)

- not seen by builders as being particularly useful

- desired by buyers, but they didn’t really know how to express their demand for it.

Project managing a house build is tough: some 20–25 subbies are required each build (with a high level of specialisation of trades), plus multiple visits from building inspectors.

Better project management can reduce the risk of the highly networked sector coming to a slow grind during peak demand periods. Also if project management is poor, then don’t hold out much hope that quality assurance management processes will be any better. (Builders will often default to ‘if you want a job done properly, then do it yourself’.)

Auckland Council building control staff struggle with significant industry quality issues, with 25%–40% of all building inspections failing. A council’s role ought to be limited to compliance (e.g. auditing quality assurance processes), but inspectors often find that quality assurance isn’t being done at all.

So councils fill the vacuum. That’s because they are liable for potentially all the harm caused by others (because of the government’s joint and several liability rule) and because they have a legally defined ‘duty of care’ to consumers. So they effectively start micromanaging builders, which in turn repels builders.

Move to proportional liability

The government needs to think more carefully about replacing the ‘joint and several liability’ rule with ‘proportional liability’ (like Australia). People and organisations including councils should be liable only for the losses they contribute, not for losses out of all proportion to what they caused. At the moment building firms are incentivised by the joint and several rule to be extremely small for two reasons. One, so that they can personally supervise build quality (rather than delegate). The other, so they can disappear from plaintiffs, and liquidate (or ring-fence assets) so that they are not left carrying all the liability caused by other people.

This change would reduce the incentives for firms to be extremely small, and will help them to achieve efficiencies of scope (i.e. different trades and skills in-house) and scale (i.e. more work). Larger firms can support more management overheads to undertake project management, quality assurance, and investment in staff. Inspectors would likely cut builders some more slack, which will improve efficiencies and help address key issues about attracting and retaining staff in the industry.

The Productivity Commission raised their concerns that current liability rules exacerbate the cottage industry structure, and thus its conduct and poor performance in its 2012 housing affordability inquiry. It asked the Law Commission to consider the impact on industry structure, conduct, and performance when advising the government on whether to keep or change the ‘joint and several liability’ rule. The Law Commission didn’t. So the advice to retain the rule that the government has received is incomplete.

Other changes needed

Other opportunities for improvement and continued development include:

- supporting large scale residential development

- investment in new production technologies, such as offsite prefabrication and Building Information Modelling (BIM)

- opening up new supply chains to mitigate any market power in the current industry (such as importing material from the USA)

- developing new avenues for product approval as per the Building Code, including adopting overseas product testing

- creating new housing typologies and design formats (e.g. modular housing and attached dwellings, which may also bring non-residential construction (i.e. commercial) techniques into the residential sector)

- developing new effective project management approaches and quality assurance

- developing new processes for building compliance, including private accreditation systems and private sector insurance to help protect consumers from risk

- supporting skills training (both new recruits/apprentices and more senior skills such as project management, business management etc).

I am also sounding out interest from other local/central government departments to co-commission analysis to assess:

- where will the resources be drawn from, and which industries might be at risk of crowd-out from an expanding construction industry[1]

- what support those industries may need for Auckland’s longer term prosperity

- where emphasis should be placed on improving the quality of construction sector regulation.

Outlook

There has been a lot of focus on how land use regulation affects Auckland’s house prices. But that may be largely overcome once Auckland Council’s Proposed Unitary Plan is updated and becomes operative, possibly by late 2016. Challenges in the residential construction sector, though, will need to be addressed if housing supply is to increase fast enough to meet demand.

[1] This may involve CGE (computable general equilibrium) modelling. The work could also build upon the following publication: Department of Labour (2011) Labour Market Adjustment in the Construction Industry, 2001–2009