I was asked give a Canterbury perspective on whether I expected government services to be cut to fund tax cuts in 2017. The answer is not as straight forward as the question.

In May 2011, only three months after the Christchurch Earthquake – our biggest natural disaster – the government announced they were intending on returning to surplus ‘one full year earlier’ than previously promised. My radar went up.

To understand why, we must go back to December 1991 when New Zealand became one of the first countries in the world to prepare its government financial statements using accrual accounting.

Accrual accounting is a style of measurement for financial reporting, more commonly used by commercial businesses. The basic premise is that instead of measuring and reporting the amount of actual cash that leaves the Crown coffers each year, instead an ‘obligation’, in the year that obligation arose (or was ‘incurred’), is recorded, so long as a reasonable dollar amount of that ‘incurred obligation’ can be estimated.

The New Zealand Treasury website notes that “Accrual information is less subject to manipulation than cash information. Because the accrual basis recognises expenses when they are incurred rather than when they are paid there are limited incentives to shift payments between periods inappropriately.”

I don’t agree.

While theoretically the only difference between the ‘accrual’ and ‘cash’ approaches should be timing, timing is everything, particularly for large expenses like earthquake recovery.

Let’s look at some practical examples.

After the Canterbury Earthquakes, the insurer AMI (later renamed Southern response) collapsed. In order stave off another finance sector collapse, the Government stepped in and pledged at least $1 billion of taxpayer funds to support AMI.

The following table shows the development of how that $1 billion has been reported using the current ‘accrual’ reporting method, compared to the old style ‘cash’ profile:

You can see that the Government has currently promised (or ‘incurred’ a future obligation) of $907m. The recognition of an additional $325 million in the 2015 financial year shows the inherent failure of accrual accounting, which is that it relies exclusively on ‘appointed actuaries’ who work for insurance companies to provide the essential and supposedly ‘independent estimate’ required.

In stark contrast, the cash reality is that the Government has only paid AMI cash of $100 million.

The difference between the ‘promise’ and the ‘reality’ is $807 million. The point being promises and estimates are cheap, quick and unreliable.

Adding the cash profile tells a much richer story, in this case one of drawing out insurance settlements over time, and arguably putting pressure on AMI to delay its insurance settlements to claimants, forcing them to ‘give in’.

Let’s look at another example.

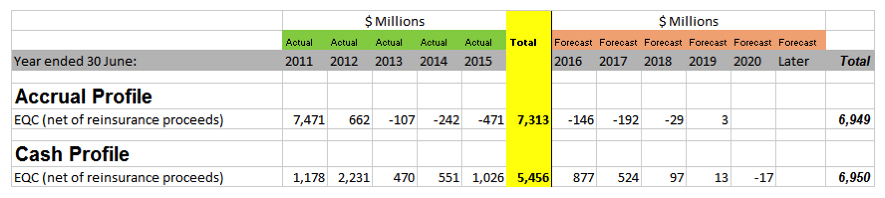

The Earthquake Commission (EQC) officially incurred most of its obligations to pay Cantabrians for earthquake damage incurred and estimated in 2011 and 2012, the financial years of the actual earthquakes.

However you can see that $1.2 billion of that obligation has been, or has been forecast to be, reversed out from 2013 through to 2018 by lowballing claimants on dwelling and land damage. Some locals will tell you these moves have manifested in dodgy repairs and long delays that will likely cost EQC more in the long term, but what all locals agree on is a deep dislike and distrust of EQC.

A ‘reversed expense’ is more easily understood as negative expenditure, or revenue.

Also again in this example you can see that not only is the cash paid out to Cantabrians from EQC being delayed, and therein creating pressures on claimants to accept less (a ‘haircut’ in financial terms) these huge reversals are allowing negative expenditure to be recorded in later years. A classic commercial creative accounting trick called “Cookie Jar” a derivative of the ‘Big Bath’ theory.

The largest single reversal of $471 million, was reversed out in 2015 – enough to get the Government across its surplus goal line. Let’s look at another example:

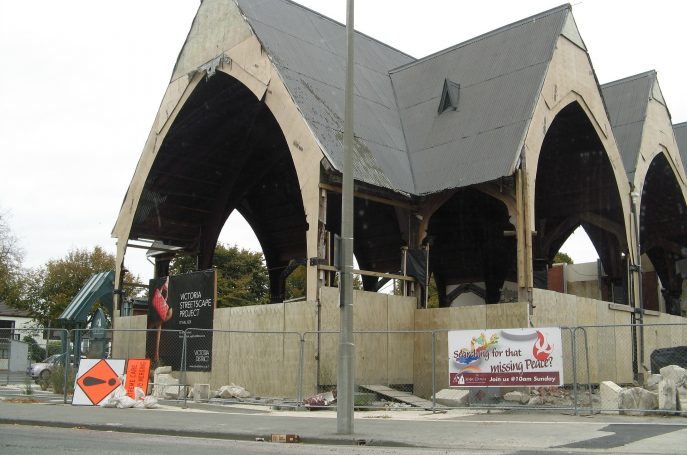

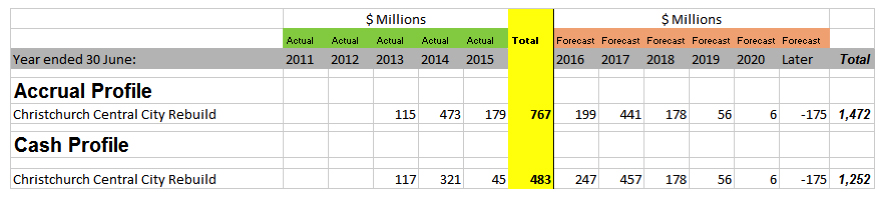

Heard anyone lamenting the slow pace of the Christchurch CBD rebuild? Well a lot of that has to do with the brakes being put on in 2015. A tiny $45 million was spent in that financial year. Major projects like the Convention Centre, the Metro Sports Facility, Stadium, Health Precinct and more have virtually ground to a standstill. The official accrual story does not reflect this, but the reality of empty sections, frustrated residents and business owners, and the cash profile, provide a fuller picture.

Here is another one to keep an eye out for: The Crown obtained the rights to all EQC land claims when it declared part of residential Christchurch a ‘Red Zone’ straight after the earthquake.

The legalities of that process are questionable, but the accounting is what I highlight here:

The Crown (Core) paid cash to Homeowners to obtain the rights to their land insurance claims from EQC (Non-Core – an ‘independent’ Crown entity) in 2011. The Crown is currently holding onto those land claim rights and will cash them in with EQC in 2017 and 2018. Hence what was an expense to one arm of the Crown in 2012 and 2013, suddenly turns into revenue in 2017 and 2018 to the other.

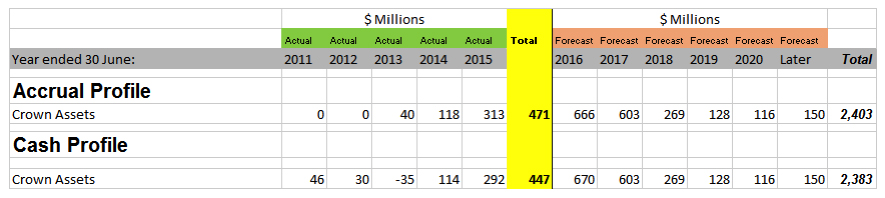

Let’s contrast this with the treatment of ‘Crown Assets’ in Canterbury. These are the schools, hospitals and courts that have to be repaired or rebuilt:

Here the Government are arguing that although there is an obligation, they can’t estimate it accurately enough to fully include the obligation in the Crown Accounts yet, so most of it hasn’t even been ‘incurred’ yet, even though the damage is plain for all to see.

Only half a billion of the $2.4 billion has been spent in ‘cash’ or ‘accrued’, instead it had been recorded as the third ugly cousin of the accrual and cash twins – the ‘forecast’. If the Government can delay coming up with reliable dollar estimates, then there is no need to recognise the cash spent OR an accrued obligation.

The last example I want to point out is slightly more complex. ‘Local Infrastructure’ represents the pipes, drains and roading in Canterbury:

While you can see again that the cash reality still lags behind the promise, it is what you can’t see in these numbers that is interesting.

In 2011 the Government managed to convince the Controller and Auditor General (who audits these numbers) that the local roads in Canterbury were not ‘damaged’ by the earthquakes, but instead the earthquakes ‘have increased the priority of the roading work in the Canterbury region, rather than created an additional liability to be recognised in the Government’s financial statements.’

To translate: a road that may have had a lifespan of 50 years a day prior to the earthquake, now only has a 10-year lifespan, but because it still has ‘life’ left, no financial obligation to fix it will be ‘incurred’ or ‘cash paid’ for another 10 years. Hence nothing is recognised at all.

This little understood fact is slowly starting to dawn on locals as road workers leave their neighbours without fixing the road, footpath and kerb and channel damage.

While it is true that there are inherent issues with timing and estimates, and cash accounting can also be manipulated, there is a strong argument for at least looking at the cash profile if you want the complete picture.

From my experience locally, it appears that politicians have used ‘creative’ tricks (usually borrowed from commercial experiences) to paint a financial picture of the Canterbury Rebuild for the rest of New Zealand, that is sometimes vastly different to the reality that Cantabrians see out their windows each day.

Early on some observed the political quake that had hit Canterbury, or predicted that it would indeed become very political.

So back to the original question: Will government services be cut to find tax cuts in 2017? From a Canterbury perspective: Only time will tell. Essential government services of roading, anchor CBD projects, schools, hospitals and EQC/insurance settlements have been endlessly delayed and constantly pushed back.

Promises remain, but promises are cheap.

The concern for the people of Canterbury is whether any ‘cash tax cuts’ in 2017 will ultimately lead to the cheap ‘accrued promises’ of the past being ‘re-estimated’ down for the future, or to translate to political speak ‘a reining in expectations’.

Government has managed to delay enough of the rebuild that either: it can’t or won’t be accurately estimated yet so has stayed off the books; or alternatively they have promised and recorded the obligation, but the actual cash, hasn’t been very forthcoming.

It seems the political narrative is currently being carefully crafted as a fight between tax cuts and debt reduction which are equally politically and electorally popular. A less popular narrative is to fulfil the accrued promises of the past, in particular that of rebuilding Christchurch, our second largest city.